Men Without Women and the Other Books I Read in September 2023

Editors Note: All the Links for the Books are Affiliate. If you buy a book, I get a little kick back. Thank you!!

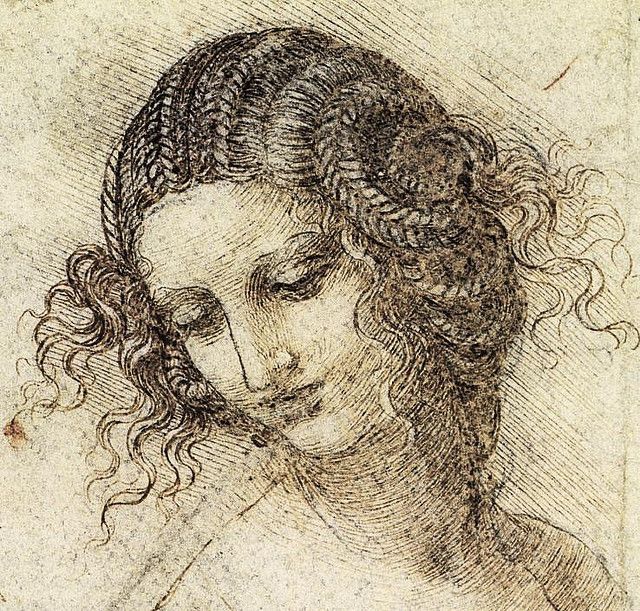

Men Without Women

Rating: 5/5

“But, as far as I can tell, even if what you do isn’t normal, it’s not bothering anybody.” “Not right now.” “So what’s wrong with that?” I said. I might have been a little upset then (at what or whom I couldn’t say). I could feel my tone getting rough around the edges. “Who says there’s anything wrong with that? If you’re not bothering anybody right now, then so what? Who knows anything beyond right now anyway? You want to speak the Kansai dialect, then you should. Go for it. You don’t want to study for the entrance exam? Then don’t. Don’t feel like sticking your hand inside Erika Kuritani’s panties? Who’s saying you have to? It’s your life. You should do what you want and forget about what other people think.” (Location 926)

But when I look back at myself at age twenty, what I remember most is being alone and lonely. I had no girlfriend to warm my body or my soul, no friends I could open up to. No clue what I should do every day, no vision for the future. For the most part, I remained hidden away, deep within myself. Sometimes I’d go a week without talking to anybody. That kind of life continued for a year. A long, long year. Whether this period was a cold winter that left valuable growth rings inside me, I can’t really say. At the time I felt as if every night I, too, were gazing out a porthole at a moon made of ice. A transparent, eight-inch-thick, frozen moon. But no one was beside me. I watched that moon alone, unable to share its cold beauty with anyone. Yesterday Is two days before tomorrow, The day after two days ago. I hope that in Denver (or some other faraway town) Kitaru is happy. If it’s too much to ask that he’s happy, I hope at least that today he has his health, and all his needs met. For no one knows what kind of dreams tomorrow will bring. (Location 1033)

“When I read this, it shocked me. If the time and place had been different, I might very well have suffered the same terrible fate. If for some reason—I don’t know why—I was suddenly dragged away from my present life, deprived of all my rights, and reduced to living as a number, what in the world would I become? I shut the book and thought about this. Other than my skills as a plastic surgeon, and the trust I’ve earned from others, I have no other redeeming features, no other talents. I’m just a fifty-two-year-old man. I’m healthy, though I don’t have the stamina I had when I was young. I wouldn’t be able to stand hard physical labor for long. The things I’m good at are selecting a nice Pinot Noir, frequenting some sushi restaurants and others where I’m considered a valued customer, choosing stylish accessories as gifts for women, playing the piano a little (I can sight-read simple sheet music). But that’s about the size of it. If I were thrown into a place like Auschwitz, none of that would help.” I agreed with him. In a concentration camp Pinot Noir, amateur piano performances, and sparkling conversational skills would be totally useless. (Location 1275)

Mindbody Prescription

Rating: 1/5

The purpose of a defense mechanism (in this case physical symptoms) is to divert people’s attention to the body, so that they can avoid the awareness of or confrontation with certain unconscious (repressed) feelings. (Location 263)

Retirement is generally “dangerous to your health,” whether you’re a man or a woman. The loss of status, the change of pattern and lifestyle almost invariably produce disturbing internal reactions that may cause emotional or physical symptoms. Some of the strongest feelings arise in the nonworking wife of a retiree. Now you have to interact with your husband all his waking hours; you may find yourself cooking three meals a day. One woman remarked that it’s like having a teenager around the house again. (Location 325)

Perfectionism is the predominant personality characteristic in many of my patients. In others, however, a closely related compulsion—the need to be good—is primary. These people are driven to be helpful, often to the extent of sacrificing their own needs. They have a desire to ingratiate, to want everyone to like them. Cultural or religious influences can enhance this tendency. Society mandates that you be a good son or daughter, a good spouse, a good parent, a congenial fellow-worker. This powerful drive, like perfectionism, seems to stem from deep feelings of inadequacy. What’s wrong with striving to be perfect and good? Doesn’t that benefit everybody? From a social and interpersonal perspective, it’s wonderful, but it also engenders great internal anger. Though we may consciously want to be and do good, the narcissistic self does not have such an imperative. Indeed, it reacts with anger at the imposition. Add to this the unconscious anger at not being fully appreciated for our efforts and, worst of all, the anger at ourselves for not living up to our own expectations. Remember, the unconscious is often irrational. A young mother with a newborn, whom she loves dearly, is very worried about doing things right, and she’s up half the night. Completely preoccupied with being a mother, she is unaware that she is unconsciously angry at the baby. Many of my patients have found it difficult to accept the idea that parents may be unconsciously angry at their children. (Location 573)

What Tech Calls Thinking

Rating: 5/5

In the dominant discourse about dropping out, several things are equated that in our own lives we know to be unequal: university equals the courses you took; the courses you took equal the courses that prepared you for eventual business success. To be clear: Zuckerberg wasn’t advising that you drop out of college when he brought up his Harvard side projects. He gave the example to illustrate the importance of being creative “outside of the jobs you’ve done.” So, once again, CNBC’s framing is off, but at the same time, Zuckerberg is perhaps revealing how he thought of college: It was his first job. He stuck it out long enough to learn what he needed to learn, but when it turned stale and a new opportunity came along, he hopped firms. Anyone who’s watched people switch jobs in tech, especially in Silicon Valley, has seen this habit in action: there is a genuine fear among young and talented tech workers in Silicon Valley of staying too long at a company whose luster has dimmed, whose tech no longer gets anyone excited. There’s the panic in people’s eyes as they admit to being at the same startup that still, even after two or three years, no one has heard of and no one cares about. (Location 259)

And what tech calls thinking may be undergoing a further shift. Fred Turner, a professor of communication at Stanford, traced the intellectual origins of Silicon Valley in his book From Counterculture to Cyberculture (2006). The generation Turner covered in that book came of age in the sixties, and if they made money in the Valley, they’re playing tennis in Woodside now; if they taught, they are mostly retiring. The ethos is changing. “As little as ten years ago,” Turner told me, “the look for a programmer was still long hair, potbelly, Gryffindor T-shirt. I don’t see that as much anymore.” The generation of thinkers and innovators Turner wrote about still read entire books of philosophy; they had Ph.D.s; they had gotten interested in computers because computers allowed them to ask big questions that previously had been impossible to ask, let alone answer. Eric Roberts is of that generation. He got his Ph.D. in 1980 and taught at Wellesley before coming to Stanford. He shaped into the form they take today two of the courses that together are the gateway to Stanford’s computer science major. CS 106A, Programming Methodologies, and 106B, Programming Abstractions, are a rite of passage for Stanford students; almost all students, whether they are computer science majors or not, enroll in one or the other during their time at the university. Roberts’s other course was CS 181, Computers, Ethics, and Public Policy. Back in the day, CS 181 was a small writing class that prepared computer scientists for the ethical ramifications of their inventions. Today it is a massive class, capped at a hundred students, that has become one more thing hundreds of majors check off their lists before they graduate. Eric Roberts left Stanford in 2015, and today teaches much smaller classes at Reed College in Portland. As Roberts tells it, the real change happened in 2008, though “it almost happened in the eighties, it almost happened in the nineties.” During those tech booms, the number of computer science majors exploded, to the point where the faculty had trouble teaching enough classes for them. “But then,” Roberts says, “the dot-com bust probably saved us.” The number of majors declined precipitously when after the bubble burst media reports were full of laid-off dot-com employees. Most of those employees were back to making good money again by 2002, but the myth of precariousness persisted—until the Great Recession, that is, which was when what Roberts calls the “get-rich-quick crowd” was forced out of investment banking and started looking back at the ship they had prematurely jumped from in 2001. When venture capital got burned in the real estate market and in finance after 2008, for instance, it came west, ready to latch on to something new. The tech industry we know today is what happens when certain received notions meet with a massive amount of cash with nowhere else to go. (Location 121)

In 2019, Jack Dorsey, the CEO of Twitter, explained in an interview with Rolling Stone that the true reason his platform was crawling with Nazi trolls was that users—his customers—were derelict in their duties. “They see things,” he complained, “but it’s easier to tweet ‘get rid of the Nazis’ than to report it.” Twitter was happy to take responsibility for Tahrir Square, it seems, but Nazis are someone else’s problem. The promotional materials the companies put out claim revolutionary potential for their platforms, but in the end, the tech giants are always happy to get out of jail free by pointing out that they are not responsible for the content on those platforms. There is a tendency in Silicon Valley to want to be revolutionary without, you know, revolutionizing anything. (Location 629)

The Way of Kings

Rating: 5/5 (ongoing)

When she drew, she didn’t feel as if she worked with only charcoal and paper. In drawing a portrait, her medium was the soul itself. There were plants from which one could remove a tiny cutting—a leaf, or a bit of stem—then plant it and grow a duplicate. When she collected a Memory of a person, she was snipping free a bud of their soul, and she cultivated and grew it on the page. Charcoal for sinew, paper pulp for bone, ink for blood, the paper’s texture for skin. She fell into a rhythm, a cadence, the scratching of her pencil like the sound of breathing from those she depicted. (Location 2064)

“Syl?” he finally prompted. “Were you going to say something?” “It seems I’ve heard men talk about times when there were no lies.” “There are stories,” Kaladin said, “about the times of the Heraldic Epochs, when men were bound by honor. But you’ll always find people telling stories about supposedly better days. You watch. A man joins a new team of soldiers, and the first thing he’ll do is talk about how wonderful his old team was. We remember the good times and the bad ones, forgetting that most times are neither good nor bad. They just are.” (Location 6009)

The eastern horizon, inverted in his sight, was growing darker. From this perspective, the storm was like the shadow of some enormous beast lumbering across the ground. He felt the disturbing fuzziness of a person who had been hit too hard on the head. Concussion. That was what it was called. He was having trouble thinking, but he didn’t want to fall unconscious. He wanted to stare at the highstorm straight on, though it terrified him. He felt the same panic he’d felt looking down into the black chasm, back when he’d nearly killed himself. It was the fear of what he could not see, what he could not know. The stormwall approached, the visible curtain of rain and wind at the advent of a highstorm. It was a massive wave of water, dirt, and rocks, hundreds of feet high, thousands upon thousands of windspren zipping before it. In battle, he’d been able to fight his way to safety with the skill of his spear. When he’d stepped to the edge of the chasm, there had been a line of retreat. This time, there was nothing. No way to fight or avoid that black beast, that shadow spanning the entirety of the horizon, plunging the world into an early night. (Location 10098)

Command and Control

Rating: 5/5 (ongoing)

If an emergency war order arrived from SAC headquarters, every missile crew officer would face a decision with almost unimaginable consequences. Given the order to launch, Childers would comply without hesitation. He had no desire to commit mass murder. And yet the only thing that prevented the Soviet Union from destroying the United States with nuclear weapons, according to the Cold War theory of deterrence, was the threat of being annihilated, as well. Childers had faith in the logic of nuclear deterrence: his willingness to launch the missile ensured that it would never be launched. At Vandenberg he had learned the general categories and locations of Titan II targets. Some were in the Soviet Union, others in China. But a crew was never told where its missile was aimed. That sort of knowledge might inspire doubt. Like four members of a firing squad whose rifles were loaded with three bullets and one blank, a missile crew was expected to obey the order to fire, without bearing personal responsibility for the result. (Location 461)

At first, the British refrained from deliberate attacks on German civilians. The policy of the Royal Air Force (RAF) changed, however, in the fall of 1941. The Luftwaffe had attacked the English cathedral town of Coventry, and most of the RAF bombs aimed at Germany’s industrial facilities were missing by a wide mark. The RAF’s new target would be something more intangible than rail yards or munitions plants: the morale of the German people. Bombarding residential neighborhoods, it was hoped, would diminish the will to fight. “The immediate aim is, therefore, twofold,” an RAF memo explained, “namely, to produce (i) destruction, and (ii) the fear of death.” The RAF Bomber Command, under the direction of Air Marshal Arthur “Bomber” Harris, unleashed a series of devastating nighttime raids on German cities… (Location 994)

The dangers of fallout were inadvertently made public when a Japanese fishing boat, the Lucky Dragon, arrived at its home port of Yaizu two weeks after the Bravo test. The twenty-three crew members were suffering from radiation poisoning. Their boat was radioactive—and so was the tuna they’d caught. The Lucky Dragon had been about eighty miles from the detonation, well outside the military’s exclusion zone. One of the crew died, and the rest were hospitalized for eight months. The incident revived memories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, sparking protests throughout Japan. When Japanese doctors asked for information about the fallout, the American government refused to provide it, worried that details of the blast might reveal the use of lithium deuteride as the weapon’s fuel. Amid worldwide outrage about the radiation poisonings, the Soviet Union scored a propaganda victory. At the United Nations, the Soviets called for an immediate end to nuclear testing and the abolition of all nuclear weapons. Although sympathetic to those demands, President Eisenhower could hardly agree to them, because the entire national security policy of the United States now depended on its nuclear weapons. (Location 2529)