Issue 55: Personal Computing Paves the Way

How the past of Personal Computing gives us a hint into the future of Personal Library Science

Dear Reader,

Sometimes, a moment happens not instantaneously, but over many seasons. Looked back on with the blessing of hindsight, there exists a discrete before and after the moment, but for those who lived it, the moment may have had a very long "during" period. Those who live in the "during" find themselves impatient, looking to be on the other side of the event, anxiously waiting for "now" to be "history". They want to live to see the thing complete. They want it to be done.

For when "now" becomes history, there is a sense of peace of mind, a complete loop, a chord that resolves into something.

History cannot be told while it is happening, therefore, not only because the people involved are too busy or too confused to puzzle it out, but because what is happening can’t be made sense of until its implications have been resolved.

-- Everything Is Obvious: *Once You Know the Answer

The curse of those who live and breathe is the task of trying to make sense of what will be – while it is – before it was.

The "During"

In issue #54, I wrote about a moment that is very much in its "during" phase, the formalization of Personal Library Science. I can not know how the story of Personal Library Science will be told by those who have the convenience of history to aid them. I can only discuss the landscape as I see it, the work completed by those who came before me, and the work being done now by me.

Someday, libraries will be fully mechanized. Then, without leaving one’s office, it will be possible to pick up the phone, dial in a code, and have the actual paper one is looking for almost instantly at hand. Something of the sort has got to happen, or our libraries will become buried in the mass of books and articles now being printed, and searching in the old way will become hopeless.

-- Pieces of the Action (1970)

The "during" is hard work, and very lonely work. There are no promises of success, and indeed, the path is one where you can't see more than three feet ahead of you and you exist on the cliff's edge of extinction by any silly mishap. The work of "during" is exhausting, and it constantly holds you taut and alert, afraid of the shadows that lurk beyond the campfire's edge.

Fortunately, the work of the edge isn't without some form of solace. The work becomes manageable, perhaps even virtuous, if we allow ourselves to commiserate with those who struggled and strived in the past to make their dreams a reality. To understand their history is to write our story.

In this issue, we'll discuss a topic that is firmly in our past. This history is not only a guide for Personal Library Science, but a key player in it's very fiber of being. We will be talking about the Personal in the portmanteau that is Personal Library Science, which comes from Personal Computing.

Personal Computing

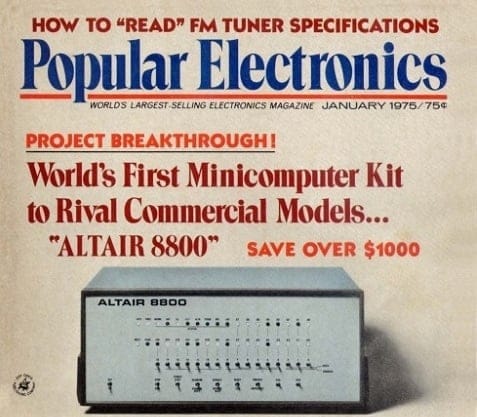

In 1975, the Altair 8800 was released. Widely considered the first personal computer, the critical advancement of computing was driven by affordability and programmability. Easier, more natural programming languages like BASIC and lower costs for hardware components made computers not massive time sharing leviathans owned only by defense departments for missile ballistic calculations and academia interested in pushing engineering and acquiring grants, but machines people could bring into their own homes.

The computer was no longer just a tool for major cost intensive purposes, but minor individualized purposes. Personal computing made computing became less about humanity, and more about humans.

As the 1990s opened, the workstation technology of the previous decade was beginning to look distinctly threatened by newer, low-cost and high-performance personal computers based on the Intel 386 chip and its descendants. For the first time, individual hackers could afford to have home machines comparable in power and storage capacity to the minicomputers of ten years earlier—Unix engines capable of supporting a full development environment and talking to the Internet.

-- The Cathedral & the Bazaar: Musings on Linux and Open Source by an Accidental Revolutionary

Scientists paved the way for engineers, engineers paved the way for hackers, hackers paved the way for hobbyists, hobbyists paved the way for everyone else. Today we live in a world where every person's phone is slightly different than their neighbors, and this is a good thing.

Idiosyncratic technology creates a natural world. Solve the problems that need solving, then get out the way.

Companies establish their DNA very early on. It can make them tremendously successful, but it can also make it hard for them to escape when what served them well in the early days doesn't serve them so well any more. I remember being an intern at IBM Research in Yorktown Heights around 1982, seeing the culture still dominated by batch processing. Even when they were doing timesharing, they talked in terms of virtual card readers and virtual card punches. Everything was still 80-column records. With DEC, it was the timesharing mentality that they never escaped. And I suppose with Microsoft it's an open question whether they'll be able to move beyond the desktop-PC mentality.

Seibel: And 20 years from now people will be talking about how Google can't get past how to sell ads on the Internet.

author's note -- ironically this was posted a few weeks before the writing of this issue: The man Who Killed Google Search

-- Coders at Work: Reflections on the Craft of Programming (2008)

What does the legacy and lessons of the rise of Personal Computing at the end of the 20th century teach us about the possible path of Personal Library Science?

Companionship

In 2020, I made the claim that the advantage of GPT models was not its ability to scale, but its ability to solve local problems. This claim began to come true years later with the release of the GPT Store (discussed in issue #42). Suddenly, individual people – not at the organization level – found themselves being able to create their own solutions to their unique, idiosyncratic problems.

Idiosyncratic technology creates a natural world.

By writing detailed instruction sets and using tactics like semantic search and function calling, LLMs leverage the effort of the individual into emergent and complex processes.

This leverage is the same leverage that made personal computing so ubiquitous, so quickly. The leverage created a new asset class, data. It gave us (you and me) superpowers of communication, and those of us who could communicate with the programs themselves (programmers) found themselves solving problems that gave them access to near limitless wealth.

It’s cheaper to reuse existing software components than to write code from scratch, which also makes it possible for entrepreneurs to start software companies with fewer up-front costs. The entire software industry owes its financial success to leveraging this arbitrage.

-- Working in Public: The Making and Maintenance of Open Source Software

Personal Library Science Is Leverage For One's Library

Personal Library Science is the leverage of LLM technology, applied to a personal library.

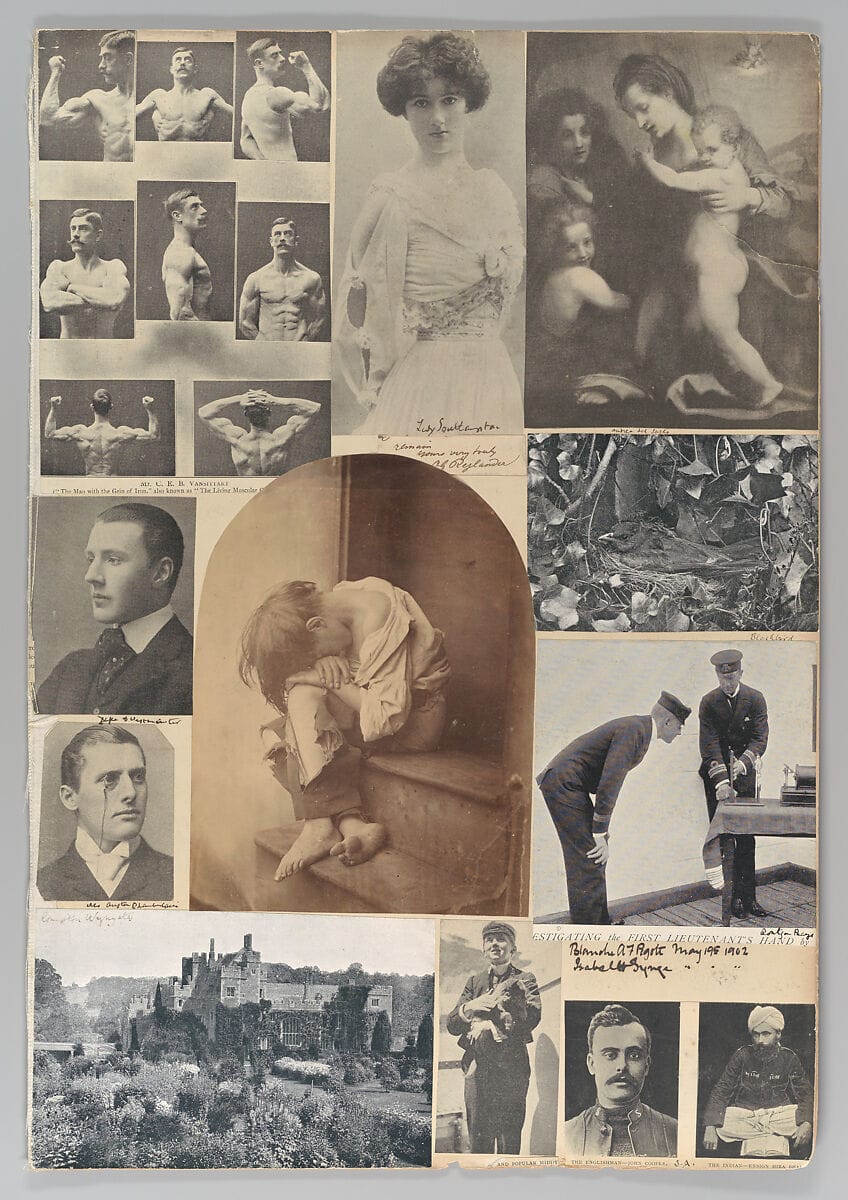

A personal library differs from a impersonal library in the fact that a personal library is an interpretation of a source material. These interpretations include: photographs from different photographers at the same event, or favorite scenes from a movie, or favorite passages from books, parts of songs that bring you to tears, etc. Importantly, these interpretations create unique sets that go on to create unique problems which require unique, idiosyncratic solutions. Sound familiar?

While a painting or a prose description can never be other than a narrowly selective interpretation, a photograph can be treated as a narrowly selective transparency. But despite the presumption of veracity that gives all photographs authority, interest, seductiveness, the work that photographers do is no generic exception to the usually shady commerce between art and truth. Even when photographers are most concerned with mirroring reality, they are still haunted by tacit imperatives of taste and conscience. The immensely gifted members of the Farm Security Administration photographic project of the late 1930s (among them Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Ben Shahn, Russell Lee) would take dozens of frontal pictures of one of their sharecropper subjects until satisfied that they had gotten just the right look on film—the precise expression on the subject’s face that supported their own notions about poverty, light, dignity, texture, exploitation, and geometry. In deciding how a picture should look, in preferring one exposure to another, photographers are always imposing standards on their subjects. Although there is a sense in which the camera does indeed capture reality, not just interpret it, photographs are as much an interpretation of the world as paintings and drawings are. Those occasions when the taking of photographs is relatively undiscriminating, promiscuous, or self-effacing do not lessen the didacticism of the whole enterprise. This very passivity—and ubiquity—of the photographic record is photography’s “message,” its aggression.

-- On Photography

In issue #54, I wrote:

...personal library science is focused on your relationship with your information. How do we store information so that it useful at a later date? How do we transform our information into new valuable assets in different creative domains? How do we do all of this while being flexible enough for the idiosyncrasies, proclivities, likes and dislikes of eight billion distinct individuals? How do we chronicle the information diet of a single person as they learn new things, interact with the world at different phases in their life? How do we make sure we can pass down our best knowledge to generations below?

Many of these questions were asked and solved by the existence of personal computing. The existence of software has had a foundational impact on the types of solutions we can create to solve these large, incalculable problems. By solving them over and over in slightly different ways that make sense to an individual the problem eventually dissolves.

In fact, I'd argue that the history of personal computing teaches us that all top down solutions are less complete – and therefore less useful – than bottom up emergent solutions.

The issue is that we are now deluged with data, our interpreter antenna is going haywire trying to calculate, to store, to relate, to understand. LLMs have changed the math entirely in this endeavor, particularly thanks to the ability to store, reference, and transform data that we find to be important, not data that others tell us is important.

Solutions such as Commonplace Bot and Quoordinates are proof points of the value of our personal libraries.

This insight is critical to our work, and the frameworks and technological gains provided by personal computing and LLMs make our task of hoping to one day understand ourselves, to use our personal libraries to secure our intellectual legacies and create our art, a bit more manageable.

Up Next

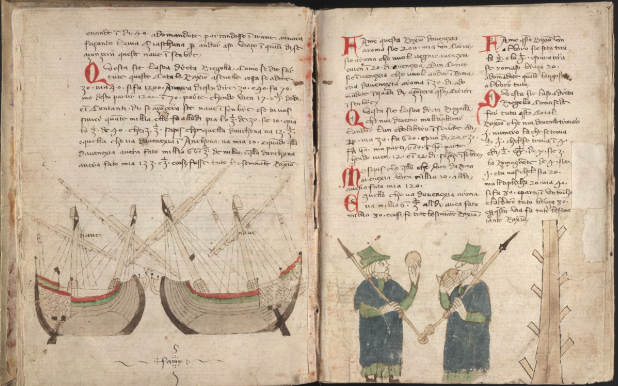

Next week, we will dive into the history of the commonplace book. The commonplace book is the foundation for the commonbase (commonplace + database) and is an integral ingredient of Personal Library Science.

Teaser

...Humanity often comes up with certain great ideas concurrently including calculus, natural selection, the use of language, etc. This concurrent creation is known as adjacent possible, and is driven by the available technology and discourse of an era. The invention of the commonplace book is no different and has lived many different lives as: the zibaldone, the miscellany, the zettelkasten, the...

Ye Olde Newsstand - Weekly Updates

Canvas Apps, speedboat accidents, the First Hokage was just a dude

Thanks for reading, and see you next Sunday!

ars longa, vita brevis,

Bram