What is Common Sense? And…How Good is It?

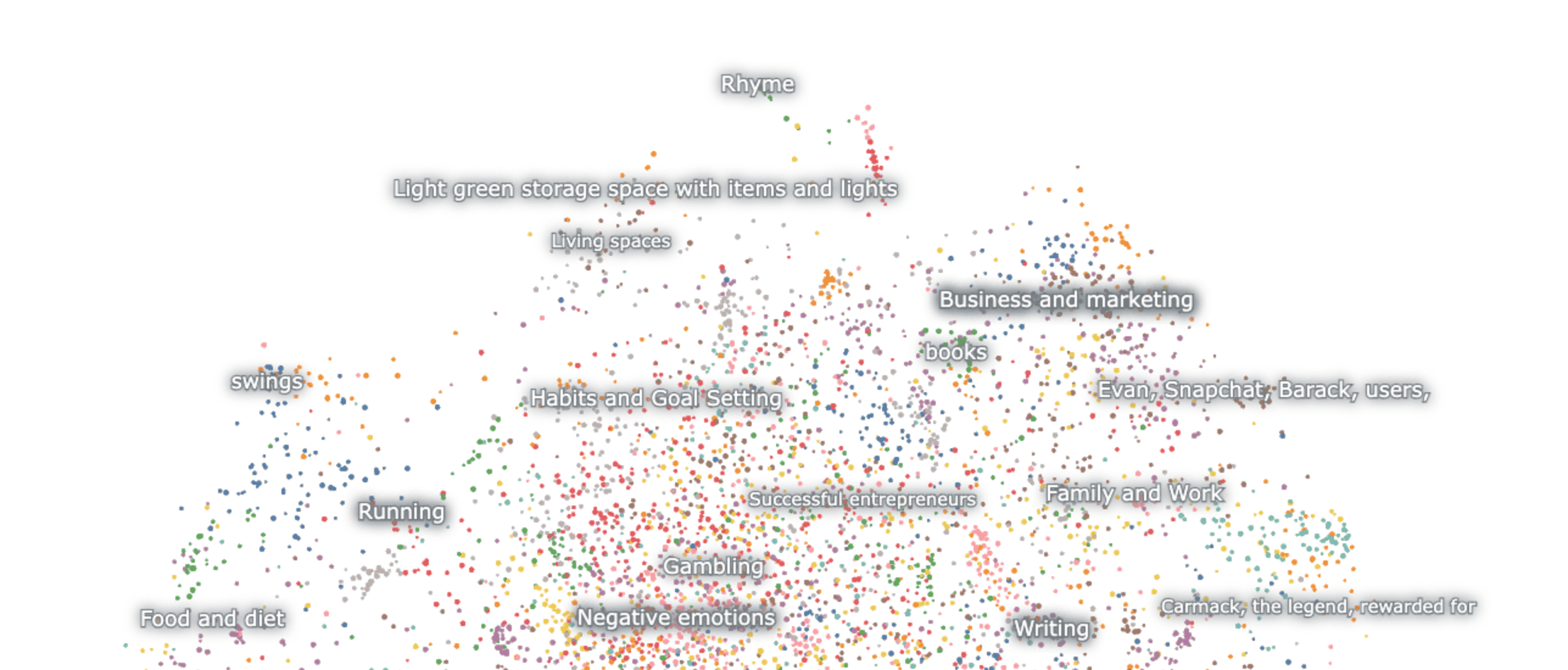

A look through quote space into common sense and theoretical knowledge

Video

What is Common Sense?

Criticizing common sense, it must be said, is a tricky business, if only because it’s almost universally regarded as a good thing—when was the last time you were told not to use it? Well, I’m going to tell you that a lot. As we’ll see, common sense is indeed exquisitely adapted to handling the kind of complexity that arises in everyday situations. And for those situations, it’s every bit as good as advertised. But “situations” involving corporations, cultures, markets, nation-states, and global institutions exhibit a very different kind of complexity from everyday situations. And under these circumstances, common sense turns out to suffer from a number of errors that systematically mislead us.

-- Everything Is Obvious: *Once You Know the Answer

similarity = 0.867170969328176

Taylor’s definition highlights two defining features of common sense that seem to differentiate it from other kinds of human knowledge, like science or mathematics. The first of these features is that unlike formal systems of knowledge, which are fundamentally theoretical, common sense is overwhelmingly practical, meaning that it is more concerned with providing answers to questions than in worrying about how it came by the answers. From the perspective of common sense, it is good enough to know that something is true, or that it is the way of things. One does not need to know why in order to benefit from the knowledge, and arguably one is better off not worrying about it too much. In contrast with theoretical knowledge, in other words, common sense does not reflect on the world, but instead attempts to deal with it simply “as it is.”

-- Everything Is Obvious: *Once You Know the Answer

similarity = 0.860661703453914

The second feature that differentiates common sense from formal knowledge is that while the power of formal systems resides in their ability to organize their specific findings into logical categories described by general principles, the power of common sense lies in its ability to deal with every concrete situation on its own terms. For example, it is a matter of common sense that what we wear or do or say in front of our boss will be different from how we behave in front of our friends, our parents, our parents’ friends, or our friends’ parents. But whereas a formal system of knowledge would try to derive the appropriate behavior in all these situations from a single, more general “law,” common sense just “knows” what the appropriate thing to do is in any particular situation, without knowing how it knows it It is largely for this reason, in fact, that commonsense knowledge has proven so hard to replicate in computers—because, in contrast with theoretical knowledge, it requires a relatively large number of rules to deal with even a small number of special cases. Let’s say, for example, that you wanted to program a robot to navigate the subway. It seems like a relatively simple task. But as you would quickly discover, even a single component of this task such as the “rule” against asking for another person’s subway seat turns out to depend on a complex variety of other rules—about seating arrangements on subways in particular, about polite behavior in public in general, about life in crowded cities, and about general-purpose norms of courteousness, sharing, fairness, and ownership—that at first glance seem to have little to do with the rule in question.

-- Everything Is Obvious: *Once You Know the Answer

similarity = 0.856078737756213

What is Thinking with Heuristics?

The unique power of heuristic reasoning lies in its ability to cope with the complex and the unexpected, to make acceptable choices when there isn’t time enough to make the ideal choice, to hunker down and keep on going when a precisely defined algorithm would be overwhelmed by the combinatoric explosion. In effect, heuristic reasoning is what allows us to go through life in a chronic state of controlled panic.

-- The Dream Machine

similarity = 0.845813891763187

This is the essence of intuitive heuristics: when faced with a difficult question, we often answer an easier one instead, usually without noticing the substitution.

-- Thinking, Fast and Slow

similarity = 0.838367719842823

To avoid mental traps, you must think more objectively. Try arguing from first principles, getting to root causes, and seeking out the third story. Realize that your intuitive interpretations of the world can often be wrong due to availability bias, fundamental attribution error, optimistic probability bias, and other related mental models that explain common errors in thinking. Use Ockham’s razor and Hanlon’s razor to begin investigating the simplest objective explanations. Then test your theories by de-risking your assumptions, avoiding premature optimization. Attempt to think gray in an effort to consistently avoid confirmation bias. Actively seek out other perspectives by including the Devil’s advocate position and bypassing the filter bubble. Consider the adage “You are what you eat.” You need to take in a variety of foods to be a healthy person. Likewise, taking in a variety of perspectives will help you become a super thinker.

-- Super Thinking: The Big Book of Mental Models

similarity = 0.814922118756365

What is a Cognitive Bias and Why is it Bad?

“listening to yourself” sounds, frankly, dangerous after reading the latest issue of Psychological Review or Wikipedia’s wonderful article, “List of cognitive biases.”

-- Don't Trust Your Gut: Using Data to Get What You Really Want in LIfe

similarity = 0.834568060300791

Table 3–1. Definitions of Cognitive Distortions 1. ALL-OR-NOTHING THINKING: You see things in black-and-white categories. If your performance falls short of perfect, you see yourself as a total failure. 2. OVERGENERALIZATION: You see a single negative event as a never-ending pattern of defeat. 3. MENTAL FILTER: You pick out a single negative detail and dwell on it exclusively so that your vision of all reality becomes darkened, like the drop of ink that colors the entire beaker of water. 4. DISQUALIFYING THE POSITIVE: You reject positive experiences by insisting they “don’t count” for some reason or other. In this way you can maintain a negative belief that is contradicted by your everyday experiences. 5. JUMPING TO CONCLUSIONS: You make a negative interpretation even though there are no definite facts that convincingly support your conclusion. a. Mind reading. You arbitrarily conclude that someone is reacting negatively to you, and you don’t bother to check this out. b. The Fortune Teller Error. You anticipate that things will turn out badly, and you feel convinced that your prediction is an already-established fact. 6. MAGNIFICATION (CATASTROPHIZING) OR MINIMIZATION: You exaggerate the importance of things (such as your goof-up or someone else’s achievement), or you inappropriately shrink things until they appear tiny (your own desirable qualities or the other fellow’s imperfections). This is also called the “binocular trick.” 7. EMOTIONAL REASONING: You assume that your negative emotions necessarily reflect the way things really are: “I feel it, therefore it must be true.” 8. SHOULD STATEMENTS: You try to motivate yourself with shoulds and shouldn’ts, as if you had to be whipped and punished before you could be expected to do anything. “Musts” and “oughts” are also offenders. The emotional consequence is guilt. When you direct should statements toward others, you feel anger, frustration, and resentment. 9. LABELING AND MISLABELING: This is an extreme form of overgeneralization. Instead of describing your error, you attach a negative label to yourself: “I’m a loser.” When someone else’s behavior rubs you the wrong way, you attach a negative label to him: “He’s a goddam louse.” Mislabeling involves describing an event with language that is highly colored and emotionally loaded. 10. PERSONALIZATION: You see yourself as me cause of some negative external event which in fact you were not primarily responsible for.

-- Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy

similarity = 0.826603767540361

To avoid mental traps, you must think more objectively. Try arguing from first principles, getting to root causes, and seeking out the third story. Realize that your intuitive interpretations of the world can often be wrong due to availability bias, fundamental attribution error, optimistic probability bias, and other related mental models that explain common errors in thinking. Use Ockham’s razor and Hanlon’s razor to begin investigating the simplest objective explanations. Then test your theories by de-risking your assumptions, avoiding premature optimization. Attempt to think gray in an effort to consistently avoid confirmation bias. Actively seek out other perspectives by including the Devil’s advocate position and bypassing the filter bubble. Consider the adage “You are what you eat.” You need to take in a variety of foods to be a healthy person. Likewise, taking in a variety of perspectives will help you become a super thinker.

-- Super Thinking: The Big Book of Mental Models

similarity = 0.814978449084254

How Do We Use the Scientific Method Day to Day?

But as frustrating as it can be for physics students, the consistency with which our commonsense physics fails us has one great advantage for human civilization: It forces us to do science. In science, we accept that if we want to learn how the world works, we need to test our theories with careful observations and experiments, and then trust the data no matter what our intuition says.

-- Everything Is Obvious: *Once You Know the Answer

similarity = 0.849901643962777

The real purpose of scientific method is to make sure Nature hasn’t misled you into thinking you know something you don’t actually know. There’s not a mechanic or scientist or technician alive who hasn’t suffered from that one so much that he’s not instinctively on guard. That’s the main reason why so much scientific and mechanical information sounds so dull and so cautious. If you get careless or go romanticizing scientific information, giving it a flourish here and there, Nature will soon make a complete fool out of you.

-- Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry Into Values

similarity = 0.829409898185019

The scientific method works best in circumstances in which the system studied can be truly isolated from its general context. This is why its first triumphs came in the study of astronomy.

-- The Real World of Technology (CBC Massey Lectures)

similarity = 0.824745276062919

How Does Science Move Forward in a Complex Messy World?

It is easy to depict a discovery, once made, as resulting from a logical, and linear process, but that does not mean that science should progress according to neat, linear and sequential rules.

-- Alchemy: The Dark Art and Curious Science of Creating Magic in Brands, Business, and Life

similarity = 0.848730067042281

But as frustrating as it can be for physics students, the consistency with which our commonsense physics fails us has one great advantage for human civilization: It forces us to do science. In science, we accept that if we want to learn how the world works, we need to test our theories with careful observations and experiments, and then trust the data no matter what our intuition says.

-- Everything Is Obvious: *Once You Know the Answer

similarity = 0.844405724135218

Through multiplication upon multiplication of facts, information, theories and hypotheses, it is science itself that is leading mankind from single absolute truths to multiple, indeterminate, relative ones.

-- Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry Into Values

similarity = 0.842365816116787

Is There One Overarching Theory in Science to Rule Them All?

Science, however, presumes no ontology. Ontologies are theories, and science—a method for evolving and testing theories—grants to no theory a special dispensation. Each theory, like each species, must compete to endure. A theory that today boasts a long reign may tomorrow, like so many erstwhile species, suffer a sudden extinction.

-- The Case Against Reality: Why Evolution Hid the Truth from Our Eyes

similarity = 0.843078905655538

The ideal that explanatory science strives for is nicely described by the quotation from Wheeler with which I began this chapter: ‘Behind it all is surely an idea so simple, so beautiful, that when we grasp it – in a decade, a century, or a millennium – we will all say to each other, how could it have been otherwise? [my italics].’ Now we shall see how this explanation-based conception of science answers the question that I asked above: how do we know so much about unfamiliar aspects of reality? Put yourself in the place of an ancient astronomer thinking about the axis-tilt explanation of seasons. For the sake of simplicity, let us assume that you have also adopted the heliocentric theory. So you might be, say, Aristarchus of Samos, who gave the earliest known arguments for the heliocentric theory in the third century BCE

-- The Beginning of Infinity: Explanations That Transform the World

similarity = 0.834313729717656

Whenever a wide range of variant theories can account equally well for the phenomenon they are trying to explain, there is no reason to prefer one of them over the others, so advocating a particular one in preference to the others is irrational.

-- The Beginning of Infinity: Explanations That Transform the World

similarity = 0.827060231335298

What is Optimization of a Scientific Theory?

One way to choose among several competing models is the Occam’s razor principle, which suggests that, all things being equal, the simplest possible hypothesis is probably the correct one. Of course, things are rarely completely equal, so it’s not immediately obvious how to apply something like Occam’s razor in a mathematical context. Grappling with this challenge in the 1960s, Russian mathematician Andrey Tikhonov proposed one answer: introduce an additional term to your calculations that penalizes more complex solutions. If we introduce a complexity penalty, then more complex models need to do not merely a better job but a significantly better job of explaining the data to justify their greater complexity. Computer scientists refer to this principle—using constraints that penalize models for their complexity—as Regularization.

-- Algorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human Decisions

similarity = 0.811555240426935

It may seem strange that scientific instruments bring us closer to reality when in purely physical terms they only ever separate us further from it. But we observe nothing directly anyway. All observation is theory-laden. Likewise, whenever we make an error, it is an error in the explanation of something. That is why appearances can be deceptive, and it is also why we, and our instruments, can correct for that deceptiveness. The growth of knowledge consists of correcting misconceptions in our theories. Edison said that research is one per cent inspiration and ninety-nine per cent perspiration – but that is misleading, because people can apply creativity even to tasks that computers and other machines do uncreatively. So science is not mindless toil for which rare moments of discovery are the compensation: the toil can be creative, and fun, just as the discovery of new explanations is. Now, can this creativity – and this fun – continue indefinitely?

-- The Beginning of Infinity: Explanations That Transform the World

similarity = 0.810235969716884

Science, however, presumes no ontology. Ontologies are theories, and science—a method for evolving and testing theories—grants to no theory a special dispensation. Each theory, like each species, must compete to endure. A theory that today boasts a long reign may tomorrow, like so many erstwhile species, suffer a sudden extinction.

-- The Case Against Reality: Why Evolution Hid the Truth from Our Eyes

similarity = 0.809941979667297

bramadams.dev is a reader-supported published Zettelkasten. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.